(Click here for background on the Supreme Court Project)

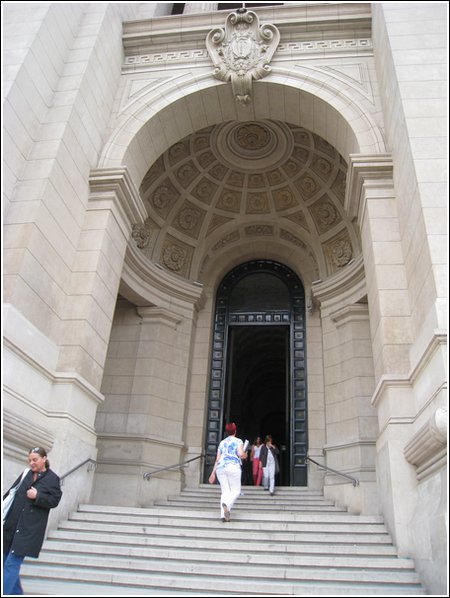

Supreme Court of Peru, Palacio de Justicia, Lima, Peru

Address: Miguel Aljovin, Lima, Peru, by Estacion Central subway (Map)

Unlike our Ecuadorian adventure, our visit to the Supreme Court of Peru didn't feature any impromptu meetings with publicity officers. Our cab driver didn't know the way to the Supreme Court--and wondered why two foreigners wanted to go there--but he did know the Sheraton Lima, which faces right across the park from the fantastic Palacio de Justicia, and we could guide him from there.

Thus, we emerged into a sunny afternoon in front of a grand neoclassical structure that takes up most of a city block and houses the upper levels of the Peruvian judiciary. According to Wikipedia, the Peruvians modeled the building off of the law courts of Brussels, and the building does have a very heavy, European feel. Foolishly, I tried to walk up the steps to the front entrance, only to be rebuffed by a uniformed clerk who insisted that if we wanted to enter, we needed to go in the side door.

The Palacio de Justicia, at night

There are no signs advising where to go as a "visitor," although there is a public entrance on the north side of the building. Unlike the grand facade, these doors are more pedestrian steel affairs, and a small crowd of litigants, attorneys and document carriers milled around waiting for admission to begin at two o'clock. We were in no hurry, and so wandered in a complete circuit around the building. To the northwest, a dirty park sat forlornly across the street from a few cantinas. Surrounding the Palacio on the west and south are the offices of government and private attorneys, both of whom were privileged to use entrances limited only to officialdom. The private offices to the south are a particularly interesting mix. Some bore clean, polished bronze plaques announcing the name of the lawyers within, while the windows of other offices were festooned with dot-matrix banners annoucing "ABOGADO" in faded grey letters.

The public doors still hadn't opened when we made it back to the public entrance, so we made our way northeast up Azangaro street. Here the shops are most definitely lawyer-focused: I have not seen so many places to buy highlighters, binders, binder clips, printing services or other paper-based products in my life. Mixed amidst these are a number of cheap coffee and sandwich shops, where it would be hard to pay more than five dollars for lunch.

Feeling well fed on ham sandwiches, we returned to find that the public doors had opened in our absence. The crowd was now slightly larger, but also slowly making its way past security. A few attorneys (or perhaps employees of attorneys), sweating in the sun outside the door in navy blue wool suits, approached us to ask if we needed counsel. They were skeptical that the guards would let us in as tourists, but we actually didn't have much trouble. This may be because the guard asked if we were attorneys, we said "yes," and he let us by without inquiring further as to our business.